“It’s not hard to make decisions when you know what your values are.” – Roy E. Disney

Values can sometimes seem like the stepchild of strategic planning. The guts of a strategic plan can include a results-oriented vision translated into specific objectives, measures and initiatives that will support it.

Values, on the other hand, can feel a bit fuzzy. Often, people think of values as a “do-gooder” thing. The exercise of defining values may feel like an exercise in identifying lofty sentiments rather than guiding day-to-day behavior.

Edgar Schein, who has made a career of studying organizational culture and values, makes a distinction between “espoused values” – the things we say we believe in – and “shared tacit assumptions” – the often unspoken assumptions about “the way things are” that actually shape our behavior. All organizations have values, whether these are explicit or not.

This last point is important. For example, Enron had a list of four values that sounded very convincing: respect, integrity, communication and excellence. There also were a number of other values, such as “consistent profits quarter over quarter no matter what,” that weren’t stated, yet were the primary drivers of management behaviors – hidden from public view until it was too late.

These kinds of values – stating things that sound nice but don’t really guide our behavior – are what we call “lobbyware.” They look good on a plaque but don’t really say anything about how we make decisions.

There’s nothing wrong with having a value based on profit—this is how businesses grow and sustain over time. I was working with the executive team of a privately-held company, defining values as part of Step 1 of the Institute’s Nine Step process, and the CEO proposed a value of “profit.” Some of his executives were mildly horrified, to say the least. They were coming from the paradigm that all values have to be “nice,” and felt that somehow focusing on profit just wouldn’t be very motivating to most employees. The CEO’s response was telling – “If we don’t make a profit, we’re out of business. And we’re all out of a job.” Similarly, in the non-profit world, we hear the slogan “No margin, no mission.”

And, all values aren’t necessarily “humanistic” attributes like teamwork, respect, or public service. Values create both an ethical and a practical compass that influences actions and decision in every-day situations. In a “lean” company like Toyota, for example, values include “Go to where the work is done and find the facts,” “Encourage Consistency,” and “Reduce Waste” – all part of a rigorous emphasis on continuous, measureable process improvement.

Ultimately, values reflect the personality of the organization, and are an important component of the organization’s culture – part of the foundational perspective we refer to as “Organizational Capacity.” As part of this, well-articulated values can be a powerful way to attract and screen new employees who are compatible with the culture of your organization.

Finally, the assessment of an organization’s strengths and weaknesses may show that the current values of the leadership or workforce are incompatible with what is needed to move forward, seize opportunities, or adapt to change. In that case, a strategic theme addressing cultural transformation may be called for. This cultural transformation may be essential to achieve other goals of the organization.

Read more about Values in The Institute Way: Simplify Strategic Planning and Management with the Balanced Scorecard.

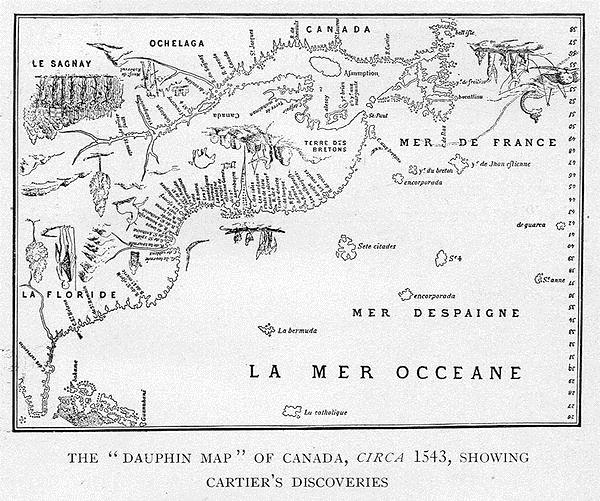

During the years we lived in Canada, my family became fond of Canadian Heritage Moments. These were sixty-second vignettes that depicted formative moments in Canadian history.

One of my favorites has the intrepid French explorer Jacques Cartier arriving in the valley of the St. Lawrence River in the year 1534 and encountering a group of Iroquois. The leader of the tribe approaches the French party and invites them to visit his nearby village. The viewer, having the benefit of English subtitles, learns that the word for village in Iroquois is “kanata.”

Cartier turns to the priest on his right and asks “What is he saying, father?” The priest hesitates a moment and then announces confidently: “He is saying that the name of this nation is Canada!” A helpful and obviously intelligent young man steps up behind Cartier and says “Begging your pardon, sir, but he’s inviting you to visit him in his village. Canada is his word for village.” The priest asserts his authority, dismissing the young man, and off they go. And the rest is history!

Enjoy the story at http://tinyurl.com/k84fsdk

When exploring new territory, it’s best to draw as much as possible on the collective intelligence of the group when assessing the situation. This is truer than ever in our organizations, and at least as true as it was in Cartier’s time. Cartier, after all, thought he was in Asia.

One of the biggest mistakes we make in strategic planning is assuming that the future will be more or less like the past. It won’t. It’s critical to articulate – and question – our assumptions about the environment we operate in, in terms of what our customers value, what our competition is offering, and the impacts of big forces like technology and the economy.

Many of our organizational ways derive from a simpler time, when we could rely on the experience of people who’d been around longer for an accurate assessment of the situation. In one of my classes, a student raised his hand and said “That’s what we call the HiPPO principle. It means that decisions are made based on the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion.”

In rapidly changing times, making strategic assessments and decisions based on what worked in the past may prove short sighted. A well-managed system for tracking and reporting strategic metrics is the compass that leaders and staff throughout the organization can use to learn from experience and align their actions in pursuit of better value for customers.

We recommend that you:

During the years we lived in Canada, my family became fond of Canadian Heritage Moments. These were sixty-second vignettes that depicted formative moments in Canadian history.

One of my favorites has the intrepid French explorer Jacques Cartier arriving in the valley of the St. Lawrence River in the year 1534 and encountering a group of Iroquois. The leader of the tribe approaches the French party and invites them to visit his nearby village. The viewer, having the benefit of English subtitles, learns that the word for village in Iroquois is “kanata.”

Cartier turns to the priest on his right and asks “What is he saying, father?” The priest hesitates a moment and then announces confidently: “He is saying that the name of this nation is Canada!” A helpful and obviously intelligent young man steps up behind Cartier and says “Begging your pardon, sir, but he’s inviting you to visit him in his village. Canada is his word for village.” The priest asserts his authority, dismissing the young man, and off they go. And the rest is history!

Enjoy the story at http://tinyurl.com/k84fsdk

When exploring new territory, it’s best to draw as much as possible on the collective intelligence of the group when assessing the situation. This is truer than ever in our organizations, and at least as true as it was in Cartier’s time. Cartier, after all, thought he was in Asia.

One of the biggest mistakes we make in strategic planning is assuming that the future will be more or less like the past. It won’t. It’s critical to articulate – and question – our assumptions about the environment we operate in, in terms of what our customers value, what our competition is offering, and the impacts of big forces like technology and the economy.

Many of our organizational ways derive from a simpler time, when we could rely on the experience of people who’d been around longer for an accurate assessment of the situation. In one of my classes, a student raised his hand and said “That’s what we call the HiPPO principle. It means that decisions are made based on the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion.”

In rapidly changing times, making strategic assessments and decisions based on what worked in the past may prove short sighted. A well-managed system for tracking and reporting strategic metrics is the compass that leaders and staff throughout the organization can use to learn from experience and align their actions in pursuit of better value for customers.

We recommend that you: