by Howard Rohm | Feb 15, 2018 | Uncategorized

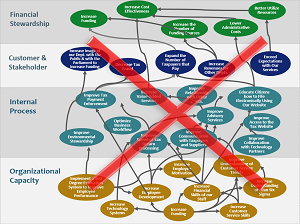

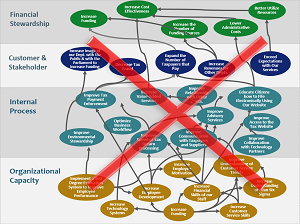

One of our clients decided to build their strategy map and balanced scorecard themselves after some training. They created a draft strategy map with 12 strategic objectives, linked together in a cause-effect chain–the strategy map–that showed how value was being created for their customers and the owners of the business. A few months after the training, the number went from 12 objectives to 32. Why? – a lack of discipline around the strategy development process and a feeling by a few folks who did not attend training that “more is better”.

One of our clients decided to build their strategy map and balanced scorecard themselves after some training. They created a draft strategy map with 12 strategic objectives, linked together in a cause-effect chain–the strategy map–that showed how value was being created for their customers and the owners of the business. A few months after the training, the number went from 12 objectives to 32. Why? – a lack of discipline around the strategy development process and a feeling by a few folks who did not attend training that “more is better”.

How many strategic objectives should there be on a strategy map? Ten, fifteen, twenty? Are more objectives better? How many are too many? How few are too few?

A strategy map is a visual representation of a strategy—it’s a hypothesis of what an organization has to do to create value for its customers and owners. For a private sector business, the owners are the shareholders; for a mission-driven organization — nonprofit or government — the “owners” at the end of the value chain are the benefiting stakeholders, e.g., members of an association, citizens of a government.

Strategic objectives, when connected in cause-effect links, represent a strategy hypothesis that can be tested and progress monitored using strategic measures of performance—KPIs—developed as part of the strategy development process. A good strategy map requires good objectives.

Objectives are used to identify measurable strategic intended results; develop KPIs that measure strategy progress; identify, prioritize and track actionable initiatives; build employee accountability; and communicate corporate vision and strategy internally and externally. We’ve identified a set of best practices for creating strategic objectives and strategy maps from our training and consulting engagements worldwide:

- Objectives are not start/stop activities or projects (those are initiatives)…objectives are continuous improvement activities that work together to produce value

- Twelve to 14 objectives are a good number for a corporate strategy map (organization size doesn’t matter here)

- Objectives indicate action and the potential for continuous improvement (Remember: strategic objectives are the DNA of your strategy—they make strategy actionable and understandable throughout the organization.)

- Objectives should be balanced among the four perspectives in a scorecard

- Objectives are “altitude sensitive”—if the strategic altitude is too high, it’s hard to translate “lofty” language into employee action…if too low, objectives will be framed in operational, not strategic, language

- Prioritized strategic initiatives, linked to each objective, should propel the organization forward toward its goals and vision

- Objectives should be measurable based on the associated intended results, to monitor progress toward accomplishment

Arguably one of the most important contributions to the science of management in the past two decades, strategy maps communicate the organization’s value proposition with clarity, both internally to employees so they can see how they “fit” in the organization, and externally to boards and other stakeholders.

Get strategic objectives and your strategy map right and your balanced strategic plan and strategy story will come alive quickly and clearly. These tools can help take your organization to the next level of performance.

You can learn more about strategic objectives and strategy mapping by reading our book, The Institute Way: Simplify Strategic Planning and Management with the Balanced Scorecard, or by attending one of our worldwide training classes.

by Howard Rohm | Jul 16, 2014 | Uncategorized

Imagine you take your car to the car dealer to get serviced. Before you give your car to the service manager you see the following performance statistics posted on the wall:

- Average time to wait for an appointment after requesting one—27 days

- Number of people who requested an appointment but didn’t get one—46,000

Not too reassuring is it. Would you leave your car or look somewhere else?

Some Veteran Administration facilities have a performance history like this. According to a recent review of the VA requested by President Obama, the agency is in deep trouble—average wait time for an appointment is 27 days and 46,000 veterans never got an appointment after requesting one. Some veterans died while waiting for appointments, although it’s not clear if the delays in medical attention contributed to the deaths.

At some VA facilities performance measurement data were misreported to make executives’ performance appear better than it was. Fraudulent performance reporting was used to help justify executive performance bonuses. (A department audit reported that three out of four facilities had a least one instance of false wait-time data and in some facilities two sets of books were being maintained.)

This type of behavior is called “gaming the system”. It’s a consequence of a culture overly focused on the wrong things (wait times) and a measurement system that emphasizes process performance over outcome performance. We shouldn’t be too surprised by the VA experience. When the wrong things are measured and incentivized, the wrong behaviors almost always result.

Focusing on the wrong measures and missing or minimizing the right measures created a climate of misreporting and deceit at some VA facilities, leading some executives to get credit for and bonuses based on reported good performance while all along the opposite seems to be true. Almost $300 million was paid out by the VA in 2013 for performance bonuses to employees, including nearly 300 senior leaders. (Maybe some of these executives should give their bonuses back to the VA for poor performance!) We’ll leave for another discussion the bigger question—what is systemically wrong at VA that encourages a behavior to keep two sets of books on performance?

Some critical questions come to mind. Where does customer satisfaction (veterans and their families are the customers) fit into the performance reporting and incentive equation? Shouldn’t satisfaction with medical service be heavily weighted in determining executive bonuses? If performance and reward are based mostly on process measures—like wait time—and wait time is being misreported, shouldn’t one assume that outcomes like effective medical care would suffer and that cheating to gain bonuses could occur?

How can an organization choose the “right” measures? Start with the end in mind (desired results/accomplishments) and work backwards through the processes that lead to the desired outcomes and to the resources required to produce the program outputs that yield the desired outcomes. Make sure the desired results are expressed in unambiguous language. Then test the developed measures to make sure you’re not measuring what doesn’t matter, or worse, measuring the wrong things and incentivizing the wrong behaviors. Whether you are a hospital, a car dealership, or any other business, government or nonprofit, the same principles apply for developing good performance measures.

The unintended consequences of doing measurement badly are, in the case of the VA, potentially life threatening. Can your organization afford to do performance measurement badly, or not at all?

You can learn more about developing measures that matter in our book,

The Institute Way: Simplify Strategic Planning and Management with the Balanced Scorecard. You can order the book on our

website or on

Amazon.

by Howard Rohm | Oct 4, 2013 | Uncategorized

Twenty-three people were waiting for the workshop to begin. The job at hand was to facilitate key managers, analysts, and program advisors through a strategic thinking process and formulate a new strategy. The organization was a four-hundred employee health care non-profit. It was 20 years old and was created around a single purpose: saving lives by processing tissue and organs for transplantation.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats were summarized into two major categories–Enablers and Challenges. I told the group that the enablers and challenges are important inputs to the strategy formulation process and critical to the next step–deciding who the organization’s customers were.

I took a quick survey. “I’m going to name different individuals and groups, and I want you to raise your hand when I mention a customer. First, I named organ donors–almost every hand went up. Transplant recipients–same thing, almost every hand. Doctors, about three quarters of the hands went up. Hospitals, same thing. Family members of a donor, same. Family of a recipient, the same.

I then asked a question: “If everyone is your customer, how can you create a business strategy that is actionable and focused?–How can you provide world-class services to so many different customers?”

The answer is–you can’t. You need to figure out who the primary customer is and how your organization can serve customer needs efficiently and effectively. Here’s how to do it.

Define

customers as the direct beneficiaries of your products and services. Define others as

stakeholders–those individuals or groups with an interest in your organization’s success (or failure if they are a business competitor!). And yes, customers are a subset of the larger group called stakeholders.

Separating customers from stakeholders allows you to focus on doing a few things well and not trying to do everything for almost everybody–a common failing that I have observed over the years in many organizations.

So who are the customers and who are the stakeholders in the example above? There are only three customers who are direct beneficiaries of the organizations products and services: a

doctor who receives a live tissue or organ product for transplantation, a hospital who receives a product from the organization for delivery to a doctor who performs the surgery, or a dentist who performs an implant. That’s it, just three–value given and value received (in the form of a payment for a product). Are others in the example important? Of course they are, but they are very invested stakeholders, not primary customers.

How did this workshop help the organization? By identifying the three primary customers, new strategies were developed that aligned directly to the mission and vision. These strategies provided strategic direction that could be made actionable with a budget and an operating plan. Then several strategic initiatives were identified that would directly improve customer-facing processes and services affecting the three primary customers. And strategic performance measures were identified, to ensure that progress was being made on the organization’s goals.

Building a strategy focused organization is about defining and connecting organization strategic elements. Identifying customers and their needs is a critical step. You can learn more about how to identify your customers and improve customer value in our new book,

The Institute Way: Simplify Strategic Planning and Management. You can order it

here or on

Amazon.

One of our clients decided to build their strategy map and balanced scorecard themselves after some training. They created a draft strategy map with 12 strategic objectives, linked together in a cause-effect chain–the strategy map–that showed how value was being created for their customers and the owners of the business. A few months after the training, the number went from 12 objectives to 32. Why? – a lack of discipline around the strategy development process and a feeling by a few folks who did not attend training that “more is better”.

One of our clients decided to build their strategy map and balanced scorecard themselves after some training. They created a draft strategy map with 12 strategic objectives, linked together in a cause-effect chain–the strategy map–that showed how value was being created for their customers and the owners of the business. A few months after the training, the number went from 12 objectives to 32. Why? – a lack of discipline around the strategy development process and a feeling by a few folks who did not attend training that “more is better”.